CHOOSING AN AFFIX

'BLACKVEIN'

What's in a name?

'BLACKVEIN'

What's in a name?

I was asked some time ago to write an article for the Lancashire, Yorkshire and Cheshire Basset Hound Club on how I choose my affix, I thought long and hard about the how I should tackle the job at hand, I have included the result as I though it might be of some interest here.................

When I was asked to write about how I choose my affix, I knew it would be very difficult to put into words! However, I hope you find it as interesting as I did when I did my research. Please note that Crosskeys was known as (North) Risca when these events took place.

When I was asked to write about how I choose my affix, I knew it would be very difficult to put into words! However, I hope you find it as interesting as I did when I did my research. Please note that Crosskeys was known as (North) Risca when these events took place.

I was born in the house I live in, as was my mother before me. It is situated in the western valley, which is or rather was, on the edge of the massive South Wales Coalfield. My family’s roots are planted firmly in the mining industry. To give you idea how deeply, both my grandfathers’ my father and all 4 of my uncles worked underground. My husband Steve’s, family was almost identical to mine. His grandfathers’, father and 4 uncles worked underground. (Although, his uncles being considerably younger than mine, worked in Risca colliery after leaving school, and found alternative work when the pit closed in the 1960’s)

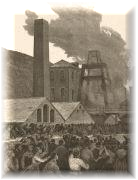

Risca Colliery - Crosskeys

It was not an easy industry to be in, 3 of our 4 grandfathers all went to work in the pits at the tender age of between 11 and 13, this was around 1900, and left when they retired. There was no mechanisation then, it was picks, shovels and hard heavy work. My maternal grandfather although an underground haulier, who worked with pit ponies, broke almost every bone in his body and retired when he was 70 in 1959. My paternal grandfather originally from the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, died as a result of coal dust in 1971, as did my poor dad in 2000.

Coal hewers and a pit pony waiting

to remove the filled coal tram

to remove the filled coal tram

Pneumoconiosis is a long, slow and painful killer whose victims fight for every breath. Steve’s maternal grandfather had a severe accident underground, which left him disabled, with one leg 4 inches shorter than the other, in addition to a chronic chest condition, he passed away in 1975 just a week before our wedding. His paternal granddad died in 1981. I remember so vividly, the blue scars those elderly men wore proudly as a testament to their years of toil within what was known locally as the “bowels of the earth”. My mum’s eldest brother too, died of as the result of an accident underground, after nearly losing a leg complications set in. Many years later he lost a very dignified battle with his illness, having suffer a very long time, his death was very painful. Seeing him suffer shattered my grandparents and my mum. He and my dad worked together on the cutters, the dirtiest job in the pit, the night he had his accident my dad was late for work and was sent to work in another district. Uncle Morgan was buried on his 49th birthday, leaving a widow and 8 children ranging in age from 23 to just 2 years old.

Geographically, the Blackvein is a small area on the lower slopes of Mynydd Machen, the mountain that is opposite my home. In spring, bluebells cover these lower slopes, a beautiful carpet of violet and blue below a canopy of mostly evergreen trees. As a youngster with my friends, we would play in the Blackvein, where there were derelict buildings of the old Blackvein Colliery. They could be very eerie and frightening to say the least. They had high ivy covered walls with occasional snatches of blue pennant stone or yellow engineering bricks and all were open to the elements, the slates and timbers lng gone, had obviously been taken to be used elsewhere. Nevertheless, it was a wonderful place to play hide and seek. The silence broken by our arrival, clambering about, we startled the birds, mostly wood pigeons. In turn the noise of their flapping wings echoed around, and added to the ghostly feel of the place. Although I would go quite happily through the wood to collect bluebells, the colliery was somewhere I never ventured alone. Sadly nothing remains of the colliery today; in fact it is now covered by a dual carriageway. It wouldn’t surprise me if the younger generation thought that the road had been there forever.

I had heard stories, as a child of the explosions in the mines, there had been so many throughout the South Wales coalfield I was a 5 year old when the last explosion happened at Six Bells Colliery in Abertillery claimed the lives of 45 men. Until I started to research the boundaries of the Blackvein with old OS maps, I didn’t realise that this small area of land was indeed named after the colliery and the deep seam of coal beneath it. I was amazed and hooked. I then went on to research it as thoroughly as I could. A story, not unique to this village but many throughout the coalfield. I felt so moved by the information I uncovered, not just the history of the Blackvein, but the anguish suffered by this small community and not once or twice but more than three times. Stunned by the sudden loss of almost a generation its men and boys, 146 poor souls in all - lost in the blink of an eye. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom to date. Most if not all of the victims are now presumably long forgotten. Although, there are still many families in the village who carry the same surnames as some of those who perished.

The colliery was built back in the 19th century, had four seams of the much sort after highest grade of steam coal (perhaps it is better known as anthracite) called the Red, Big Vein Risca, (both sunk prior to 1816) Rock Vein (sunk in1822), and the New Risca Nine Feet (or Blackvein as it became known locally), opened in 1845 to work this very rich seam at 186 yards. This “Black Vein” its thickness varied, but at Risca was between 9 and 10 feet. The seam of coal was traceable throughout the principal part of the South Wales coal basin, but varied in depth, and was known by different names. For many years it was the only this seam from the four which was worked at Risca (presumably because it was the most productive). Because of it gaseous nature pits that worked the Black vein seam were known as fiery pits and many of the explosions occurred in Collieries working this seam. There had been 3 explosions in the pit, two in 1842 killing 5, in 1846 an explosion at this pit caused by the naked flame of a candle igniting a pocket of firedamp, cost the lives of 35 men. Two men died in an accident in 1849, a year later three men were killed and eight more badly burned in a gas explosion. Just three years later in 1853 a further 10 lives were lost in another explosion. Because of the large number of fatal accidents the colliery became known as the "death pit". During 1858 mechanical means of ventilation was installed, this replaced the previous furnace method. The lesson of the earlier explosions was ignored and naked lights were still being used underground at this pit with disastrous consequences, when on 1st of December 1860 yet another explosion took the lives of 146 men and boys.

At first, reports had the number as high as 304. What was known was the men had descended to pit bottom at 4.30am earlier than usual, it was Saturday so they could leave at dinnertime. Sixty or so men who had been working at or near pit bottom, or had managed to scramble there, were winched to the surface immediately after the blast. They were so badly shocked and some severely burnt, it gave slight hope of recovery of the remainder, and their statements were incoherent as to what state the deeper workings were in.

As the air cleared the rescue operations began. Conditions were bad. Teams could only work for short periods before they were forced to the surface to rest. Some reported the scenes of horror that faced them. The stories of the destruction of human life were very harrowing. The dead and ding huddled together. The traces of a violent struggle for life before they were hit by the scorching were unmistakable. The explosion had occurred some distance from the pit-bottom and had caused a huge roof fall. The approach roads to the fall area did not have the vast damage expected from such a violent explosion. The rescuers made it quite clear that little hope could be held out for the men beyond this fall, as no fresh air could be reaching them.The main road in this colliery followed the natural dip of the Blackvein seam into the coal basin and off this "slope" other districts were driven. It was in one of these districts that the explosion occurred. The blast brought down a huge fall, which cut off the ventilation causing the after-damp to be trapped.

Meanwhile checks on the number of men down the pit that morning were put at 199. Sixty or so men had been winched up, leaving 130 still to be reached. By now, the corpses found between pit-bottom to the fall were being brought back to the surface. Eleven were taken up, but the horror, anxiety and distress proved to be too much. As bodies were taken from the cage, the eager pressed forward to see if they could recognise in the features of the dead, that of a loved one, then occasionally a loud scream, as some poor creature recognising their father, husband or son , in the ghastly corpses before them. The practise was immediately stopped and the bodies were assembled at pit-bottom. The bodies of 28 horses, also killed I the blast, had been hauled to the sides and a small hole had been carefully scrapped through the fall, for the rescue work to continue. This work was to go on for some days.

An inquest was initiated on the Tuesday after the disaster, simply to identify the bodies recovered to date, and then adjourning, to reconvene as required. The inquest proper began later that month and lasted until February. There was much speculation about the cause of the disaster; the one given most prominence in the press was that illegal smoking had most likely taken place, with a naked light igniting a pocket of gas. This was borne out, according to the press, by pipe and tobacco being found on four separate bodies!

Experts were called in to explain the gaseous nature of the pit, however, the searching inquiry revealed no obvious source of ignition. After many days the inquiry was terminated and the verdict given. The men had died from the effects of an explosion of firedamp that was suddenly given off in a third heading, but there was no evidence to show how the gas was ignited.

Various recommendations in the form of increasing air intake and stricter security checks were to be made. The inquest was finally adjourned. This was the worst mining disaster recorded to date. Most of the victims succumbed to the after-damp, but over 60 of the bodies recovered were so badly burned or disfigured they were unable to be identified. These brave men had been buried in a special cemetery, they were buried in a communal grave without coffins on the mountainside above the colliery. A piece of ground had been selected following an arrangement between the Colliery Manager and Lord Tredegar’s Estate Manager, and a special dispensation had been granted by the Bishop of Llandaff for immediate burial.

On the morning of Saturday December 1st 1860 a terrible tragedy, indeed a calamity of a fearful and overwhelming character occurred in this village of Crosskeys, also known then as North Risca. One that claimed the lives of 146, which left 51 widows, 120 fatherless children - 66 were under 5 years of age, and 8 dependant parents.

I was lucky enough to acquire a copy of the general report on the Risca Coalfield and the Appendix regarding the explosions in the Risca Coalfield. Sadly there would be another two explosions at the nearby Risca Colliery, (sunk on the same seam of coal just over ½ a mile away to the northeast), one in July 1880, which would claim the lives of 119 and the other just eighteen months later claimed another 4. The total lost in this tiny village in 5 explosions a staggering 309. What price life? When coal was being sold to Swansea Iron Works at 10 tons for 32/- (shillings), today’s equivalent £1.60. The social climate of the day was reflected in a newspaper report of the financial loss incurred by the mine owner, with the death of 28 pit ponies, the value of which was estimated at almost £1,000

I also acquired a list of explosions and losses of life. There were five other explosions greater in magnitude than that of the Black Vein; Ferndale in the Rhondda Valley in November 1867 claimed 178 lives. In September 1878, just over 1½ miles northeast of Crosskeys at Abercarn an explosion claimed 298. In February 1890 Llanerch claimed 170 lives. 1894 Cilfynydd claimed 276 lives and lastly on October 13th 1913, 436 lost their lives at Senghenydd. All as a direct consequence of this one seam of coal!

Senghenydd was undoubtedly the worst disaster in the history of the South Wales Coalfield, probably the worst in mining history in this country. During the 90 years between 1837 and 1927 in total 3589 miners, some as young as 9 years, lost their lives in colliery disasters in North Wales, South Wales and Monmouthshire .

Their fitting epitaph reads:

It was not just the men who suffered at the hands of the industrialists, their women and children faired no better. My mum raised me to be proud of this heritage and after reading the reports of these dreadful disasters I understand why. I have watched the old film “How Green was my Valley” many, many times. I saw it again quite recently, knowing all these facts as I now do, I saw it through new eyes.

By choosing BLACKVEIN as my affix, I hope it will serve in some small way, as a tribute to those brave men, their women and children, all long gone and probably forgotten by the vast majority of the community in which they all played a part.

Tina Watkins

(March 2001)

I had heard stories, as a child of the explosions in the mines, there had been so many throughout the South Wales coalfield I was a 5 year old when the last explosion happened at Six Bells Colliery in Abertillery claimed the lives of 45 men. Until I started to research the boundaries of the Blackvein with old OS maps, I didn’t realise that this small area of land was indeed named after the colliery and the deep seam of coal beneath it. I was amazed and hooked. I then went on to research it as thoroughly as I could. A story, not unique to this village but many throughout the coalfield. I felt so moved by the information I uncovered, not just the history of the Blackvein, but the anguish suffered by this small community and not once or twice but more than three times. Stunned by the sudden loss of almost a generation its men and boys, 146 poor souls in all - lost in the blink of an eye. It was the worst mining disaster in the United Kingdom to date. Most if not all of the victims are now presumably long forgotten. Although, there are still many families in the village who carry the same surnames as some of those who perished.

The colliery was built back in the 19th century, had four seams of the much sort after highest grade of steam coal (perhaps it is better known as anthracite) called the Red, Big Vein Risca, (both sunk prior to 1816) Rock Vein (sunk in1822), and the New Risca Nine Feet (or Blackvein as it became known locally), opened in 1845 to work this very rich seam at 186 yards. This “Black Vein” its thickness varied, but at Risca was between 9 and 10 feet. The seam of coal was traceable throughout the principal part of the South Wales coal basin, but varied in depth, and was known by different names. For many years it was the only this seam from the four which was worked at Risca (presumably because it was the most productive). Because of it gaseous nature pits that worked the Black vein seam were known as fiery pits and many of the explosions occurred in Collieries working this seam. There had been 3 explosions in the pit, two in 1842 killing 5, in 1846 an explosion at this pit caused by the naked flame of a candle igniting a pocket of firedamp, cost the lives of 35 men. Two men died in an accident in 1849, a year later three men were killed and eight more badly burned in a gas explosion. Just three years later in 1853 a further 10 lives were lost in another explosion. Because of the large number of fatal accidents the colliery became known as the "death pit". During 1858 mechanical means of ventilation was installed, this replaced the previous furnace method. The lesson of the earlier explosions was ignored and naked lights were still being used underground at this pit with disastrous consequences, when on 1st of December 1860 yet another explosion took the lives of 146 men and boys.

At first, reports had the number as high as 304. What was known was the men had descended to pit bottom at 4.30am earlier than usual, it was Saturday so they could leave at dinnertime. Sixty or so men who had been working at or near pit bottom, or had managed to scramble there, were winched to the surface immediately after the blast. They were so badly shocked and some severely burnt, it gave slight hope of recovery of the remainder, and their statements were incoherent as to what state the deeper workings were in.

As the air cleared the rescue operations began. Conditions were bad. Teams could only work for short periods before they were forced to the surface to rest. Some reported the scenes of horror that faced them. The stories of the destruction of human life were very harrowing. The dead and ding huddled together. The traces of a violent struggle for life before they were hit by the scorching were unmistakable. The explosion had occurred some distance from the pit-bottom and had caused a huge roof fall. The approach roads to the fall area did not have the vast damage expected from such a violent explosion. The rescuers made it quite clear that little hope could be held out for the men beyond this fall, as no fresh air could be reaching them.The main road in this colliery followed the natural dip of the Blackvein seam into the coal basin and off this "slope" other districts were driven. It was in one of these districts that the explosion occurred. The blast brought down a huge fall, which cut off the ventilation causing the after-damp to be trapped.

Meanwhile checks on the number of men down the pit that morning were put at 199. Sixty or so men had been winched up, leaving 130 still to be reached. By now, the corpses found between pit-bottom to the fall were being brought back to the surface. Eleven were taken up, but the horror, anxiety and distress proved to be too much. As bodies were taken from the cage, the eager pressed forward to see if they could recognise in the features of the dead, that of a loved one, then occasionally a loud scream, as some poor creature recognising their father, husband or son , in the ghastly corpses before them. The practise was immediately stopped and the bodies were assembled at pit-bottom. The bodies of 28 horses, also killed I the blast, had been hauled to the sides and a small hole had been carefully scrapped through the fall, for the rescue work to continue. This work was to go on for some days.

An inquest was initiated on the Tuesday after the disaster, simply to identify the bodies recovered to date, and then adjourning, to reconvene as required. The inquest proper began later that month and lasted until February. There was much speculation about the cause of the disaster; the one given most prominence in the press was that illegal smoking had most likely taken place, with a naked light igniting a pocket of gas. This was borne out, according to the press, by pipe and tobacco being found on four separate bodies!

Experts were called in to explain the gaseous nature of the pit, however, the searching inquiry revealed no obvious source of ignition. After many days the inquiry was terminated and the verdict given. The men had died from the effects of an explosion of firedamp that was suddenly given off in a third heading, but there was no evidence to show how the gas was ignited.

Various recommendations in the form of increasing air intake and stricter security checks were to be made. The inquest was finally adjourned. This was the worst mining disaster recorded to date. Most of the victims succumbed to the after-damp, but over 60 of the bodies recovered were so badly burned or disfigured they were unable to be identified. These brave men had been buried in a special cemetery, they were buried in a communal grave without coffins on the mountainside above the colliery. A piece of ground had been selected following an arrangement between the Colliery Manager and Lord Tredegar’s Estate Manager, and a special dispensation had been granted by the Bishop of Llandaff for immediate burial.

On the morning of Saturday December 1st 1860 a terrible tragedy, indeed a calamity of a fearful and overwhelming character occurred in this village of Crosskeys, also known then as North Risca. One that claimed the lives of 146, which left 51 widows, 120 fatherless children - 66 were under 5 years of age, and 8 dependant parents.

I was lucky enough to acquire a copy of the general report on the Risca Coalfield and the Appendix regarding the explosions in the Risca Coalfield. Sadly there would be another two explosions at the nearby Risca Colliery, (sunk on the same seam of coal just over ½ a mile away to the northeast), one in July 1880, which would claim the lives of 119 and the other just eighteen months later claimed another 4. The total lost in this tiny village in 5 explosions a staggering 309. What price life? When coal was being sold to Swansea Iron Works at 10 tons for 32/- (shillings), today’s equivalent £1.60. The social climate of the day was reflected in a newspaper report of the financial loss incurred by the mine owner, with the death of 28 pit ponies, the value of which was estimated at almost £1,000

I also acquired a list of explosions and losses of life. There were five other explosions greater in magnitude than that of the Black Vein; Ferndale in the Rhondda Valley in November 1867 claimed 178 lives. In September 1878, just over 1½ miles northeast of Crosskeys at Abercarn an explosion claimed 298. In February 1890 Llanerch claimed 170 lives. 1894 Cilfynydd claimed 276 lives and lastly on October 13th 1913, 436 lost their lives at Senghenydd. All as a direct consequence of this one seam of coal!

Senghenydd was undoubtedly the worst disaster in the history of the South Wales Coalfield, probably the worst in mining history in this country. During the 90 years between 1837 and 1927 in total 3589 miners, some as young as 9 years, lost their lives in colliery disasters in North Wales, South Wales and Monmouthshire .

Their fitting epitaph reads:

It was not just the men who suffered at the hands of the industrialists, their women and children faired no better. My mum raised me to be proud of this heritage and after reading the reports of these dreadful disasters I understand why. I have watched the old film “How Green was my Valley” many, many times. I saw it again quite recently, knowing all these facts as I now do, I saw it through new eyes.

By choosing BLACKVEIN as my affix, I hope it will serve in some small way, as a tribute to those brave men, their women and children, all long gone and probably forgotten by the vast majority of the community in which they all played a part.

Tina Watkins

(March 2001)

At 9.30am on December 1st 1860, a noise like distant thunder was heard echoing through the valley. The source was the Black Vein Colliery. Rumours spread like wildfire through the village, and soon the top-pit was crowded with relatives eager for news. Their worse fears had been confirmed there had been a violent explosion. All local surgeons and doctors were summoned and rushed to the colliery, later followed by those from farther a field.

It is situated on the opposite side of the valley surrounded by evergreens, just below the forestry line and above what was then a very busy canal, over looking where they had lived and died. To this day, although the trees are larger, the hustle and bustle of the canal long gone, replaced by the noise of cars, lorries and buses on the two buy roads below. The view of the valley is slightly obscured now by the growth of the trees on the banks of the canal, but the peace and tranquillity I found there was truly amazing.

A sudden change, at God’s command they fell;

They had no chance to bid their friends farewell;

Swift came the blast; without warning given;

And bid them haste to meet their God in Heaven.

They had no chance to bid their friends farewell;

Swift came the blast; without warning given;

And bid them haste to meet their God in Heaven.

There is no fitting accolade for these miners now, or for their families who were left to struggle. There was no government assistance then; many lived in houses belonging to the colliery. These were a proud people, who had been considered and sometimes treated even worse than the slaves in the southern states of America. The only option open to the if they couldn’t manage was bleak indeed, the workhouse - Wooliston House as it was known then, which would later become St. Woolos Hospital.

Blackvein Explosions Death Roll - 14th January 1846

|

Name Attwell John Banfield, Thomas Bath, John Bryant, William Collier Charles Crook, James Curtis, George Danks, Daniel Fudge, Isaac Gullock, James Hearns, Charles Jones.Elias Lovel, Isaac Pool.John Silcox, Samuel Thomas, William Williams, George |

young man, unmarried young son of George yound man unmarried son of Isaac Bryant young man unmarried young man unmarried young man unmarried young man unmarried Wife & 5 daughters young man unmarried young man unmarried young man unmarried |

Name Banfield, George Banfield, George Bryant, Isaac Bryant, Samuel Crook, Emanuel Crook, John Danks, John Danks, John Gambel, James Harrison, William Hodges, Jesse Lane, James Pike, James Powell, John Summers, George Walls, John Woodward, Thomas |

Father of George & Thomas Young son of George Wife and Family Son of Isaac Bryant Wife and Family Son of Daniel Danks Wife and 1 child young man unmarried Wife and 1 child Wife and 2 children Wife and 2 children Married |

Death Roll 12th of March 1853

|

Bryant, Aaron-- Darke, Samuel-- Davies, Thomas Moore, Moses Purnell, George |

12 12 11 |

Bryant, Joseph-- Davies, Rees Jenkins, Solomon Phillips, George Williams, John |

24 19 |

Death Roll 1st December 1860

|

Name & Age Bailey, David--Aged 27, After Damp Bannfield, John--Aged 40, After Damp Banfield, Joseph- Banfield, William-- Bateman, Isaac-- Bateman, Levi- Bath, William--Aged 31, After Damp Bath, Thomas--Aged 15, After Damp Beddoe, Evan-Aged 43, Beddoe, Stephen--Aged 17, After Damp Bevan, William- Binding, Elijah-Aged 36, After Damp Binding, Enock--Aged 34, After Damp Binding, Joshua--Aged 36, Burnt Bowen, Joseph- Brace, Mark- Brimble, James--Aged 35, After Damp Brimble, Thomas--Aged 12, After Damp Brimble, William--Aged 13, Burnt Britain, Benjamin--Aged 22, After Damp Bryant, Moses--Aged 49, After Damp Bullock Thomas- Chivers, Samuel-- Court, Henry--Aged 13, After Damp Cousener, James--Aged 28, After Damp Cox, Charles-- Crew, John--Aged 34, Burnt Crew, Emanuel--Aged 34, After Damp Davies, Alfred--Aged 24, After Damp Davies, Hopkin-- Davies, William--Aged 35, Burnt Davies, William-- Davies, William--Aged 22, Burnt Edwards, Henry--Aged 39, After Damp Edwards, Jonathan--Aged 29, After Damp Edwards, David-- English, Edward--Aged 41, After Damp Evans, Thomas--Aged 20, After Damp Evans, Charles-- Evans, Joseph-- Evans, Isaac-- Fisher, George--Aged 18, After Damp Fisher, James-- Fisher, John-- Golding, George--Aged 23, After Damp Golding, Henry-- Gough, George--Aged 18, After Damp Giffiths, John--Aged 23, After Damp |

Name & Age Grindle, James-- Grindle, Joseph-- Gullick, Frederick-- Hale,Charles-- Aged 34, After Damp Hale, William-- Hammond, James--Aged 25, Burnt Harris, John-- Aged 41, After Damp Harris, John--Aged 32, Burnt Harris, William--Aged 43, After Damp Holder, Edwin-- Aged 21, After Damp Hughes, William--Aged 40, Burnt Hughes, Morgan--Aged 39, Jacquey, Joseph-- James, Henry--Aged 45, Burnt Jenkins,David--Aged 28, After Damp Jenkins, Phillip--Aged 22, After Damp Jenkins, William--Aged 24, After Damp Jenkins, Thomas--Aged 24, After Damp Jenkins, Richard- John, William--Aged 23, After Damp Jones, William--Aged 42, After Damp Jones, JohnAged --16, After Damp Jones, John--Aged 29, After Damp Jones, Thomas-- Jones, Thomas--Aged 21, Jones, William-- Jones, John-- Kealing, William--Aged 18, King, Nathaniel-- Ledbury, Charles--Aged 24, Lewis, James --Aged 41, After Damp Lewis, George--Aged 19, After Damp Lewis, William--Aged 28, Burnt Lippiett, John-- Morgan, John--Aged 35, After Damp Murray, John--Aged 23, After Damp Nelmes, Thomas--Aged 22, Burnt Newport, George--Aged 27, Burnt Nicholas, James--Aged 17, After Damp Norris, Frederick-- Aged 11, After Damp Parry, Aaron--Aged 15, After Damp Pearce, George--Aged 13, Burnt Perry, William--Aged 13, Phillips, John--Aged 35, After Damp Phillips, John- - Phillips, James-- Aged 20, Phillips, John-- Aged 26, After Damp Pike, George--Aged 52, After Damp |

Name & Age Plumber, James- Pritchard, James --Aged 15, After Damp Pritchard, Jenkin--Aged 27, After Damp Prosser, Thomas --Aged 22, After Damp Purnell, Henry-- Rees, Daniel--Aged 17, After Damp Rees, Abraham--Aged 31, Rees, Rees Morgan--Aged 27, Robbins, George-Aged 38, After Damp- Roberts, Gethin-- Rosser, Thomas-- Sage, Isaac-- Aged 32 Sage, George-- Sage, John-- Saunders, Isaac--Aged 42, After Damp Saunders, Llewellyn--Came Out Alive, but died Skidmore, George--Aged 35, After Damp Thomas, Llewellyn--Aged 15,Burnt Thomas, Henry--Aged 11 Turner, James-- Vizard, Thomas-- Watkins, Nathaniel-- Watson, Isaac-- Watson, Abraham--Aged 32, After Damp Watson, Isaac--Aged 12, After Damp Watson, George-- Aged 10, After Damp Watts, John--Aged 15, Webb, George -- Aged 40, West, John--Aged 24, West, Joseph--Aged 13, West, George--Aged 11, White, Frederick-- White, Charles--Aged 17, After Damp Wilkins, Daniel-- Aged 41, Burnt, Williams, John--Aged 26, Burnt Williams, William--Aged 17, After Damp Williams, John--Aged 31, After Damp Williams, John--Aged 17, After Damp Williams, William--Aged 55, After Damp Williams, William-- Williams, Edmund-- Williams, Thomas-- Wilson, William--Aged 18, Burns Wilton, John--Aged 29, After Damp Wilton, William--Aged 12, After Damp Woolley, John-- Aged 17, Burnt Four others (unnamed) died later of their injuries. |

Web Design and Maitenance: Blackvein Basset Hounds © All Rights Reserved

"Grant unto them eternal rest,

O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them." Amen.

O Lord, and let perpetual light shine upon them." Amen.